Elixir/OTP Supervision

I’ve gotten questions over time about process supervision in Elixir. There’s a lack of clarity for some developers. This is especially true for companies that adopt Elixir. There are probably a few people (if you’re lucky) who know Elixir to some level. But the majority of developers that are onboarded will not know anything about the language.

One of the things that I’ve found is the most confusing and usually misused relates to supervision of processes. There are actually plenty of resources available to learn from. I provided some links in the References at the end of this post. A lot of them are probably more insightful than this post. However, I decided it might help some developers new to Elixir if I created some sample code to accompany the description of what’s going on. The idea was that new developers could use this as a basis to play around with the concepts.

The code for this blog post is in a github repo at https://github.com/fmcgeough/elixir-supervision. Assuming you have asdf and the Elixir and Erlang plug-ins installed you can install on your system with:

$ git clone https://github.com/fmcgeough/elixir-supervision

$ asdf install

$ mix deps.get

$ iex -S mix

iex>

What is a Process?

In Elixir (or Erlang) all code runs in a “process”. Processes are isolated from each other. They communicate by sending messages to each other. Elixir’s processes are not O/S processes. Processes in Elixir are extremely lightweight in terms of memory and CPU (even compared to threads as used in many other programming languages). Because of this, it is not uncommon to have tens or even hundreds of thousands of processes running simultaneously.

You can read about processes in the Elixir Documentation.

Some General Info About Processes

Processes are identified by a pid. When you start a process the system returns a pid. For our purposes a pid can be considered an opaque data structure. A pid is like an address. It allows a process to send a message to another process.

If you want to know the inner details of a process then you can read more about it, of course. It’s general structure is described in an OTP header file as:

* PID layout (internal pids):

*

* |3 3 2 2 2 2 2 2|2 2 2 2 1 1 1 1|1 1 1 1 1 1 | |

* |1 0 9 8 7 6 5 4|3 2 1 0 9 8 7 6|5 4 3 2 1 0 9 8|7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0|

* | | | | |

* +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

* |n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n n|0 0|1 1|

* +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

*

* n : number

A process can also be identified in a couple other ways. One of the ways used in the demo code is by name. The name is a unique atom. A module name is an atom and is used in many cases but you can use whatever atom you think makes sense for your application.

The test code uses atoms to identify processes. A process name can be converted to a pid by calling: Process.whereis/1. You can read about that in the Elixir documentation.

What’s Supervision?

A supervisor is a process. It’s job is to be in charge of other processes. These are thought of as its children. A supervisor can start processes. It then uses some facilities built into OTP (linking, monitoring, trapping exits) to allow the supervisor to “know” that something bad happened to one of its children.

Any process that isn’t a supervisor falls into the general category “worker”.

Supervising workers allows the supervisor to possibly restart the worker if it encounters something unexpected. It ensures that when things are shutdown (whether the entire app or a process tree) that the workers are shutdown in a particular order.

Here’s an important quote from “Learn you some Erlang for great good!”

Supervisors can supervise workers and other supervisors, while workers should never be used

in any position except under another supervisor

Is this always true? Well… no. There are circumstances where you wouldn’t want to follow this rule. But you should only violate it if you have a very good grasp on supervision and a very good well-understood reason for doing so before you violate it.

Strategies for Supervision

A Supervisor can be written to start its children with different strategies. These are:

- :one_for_one

- :one_for_all

- :rest_for_one

In Erlang there is another option - :simple_one_for_one. This was in older versions of Elixir but it was deprecated. People that used that strategy before moved to DynamicSupervisor in Elixir.

Options

:one_for_one

The most common strategy you’re likely to run into. The idea is that each worker (process) that is a child of a supervisor is totally independent. If they die the supervisor should restart just the child that died.

This means that you can’t have dependencies between the children. They are independent of each other.

:one_for_all

This is the strategy to use if all the children are dependent on each other. What we want in that case is that if any one of the processes dies then all the children should be restarted.

:rest_for_one

This strategy maybe a bit harder to understand but it can be quite useful. This is used if you have one child process that is absolutely vital for all the other children. If it dies then all the children must be restarted. This continues in the order that you supply the children. This is harder to explain then it is to demonstrate. Its demonstration is below.

Testing

If you followed the instructions above you should have an iex session open for the project. There’s code in the project that will test each strategy.

Each module that has the different types of supervision has the following functions available:

- test_kill_all(order) - where order is set to :asc or :desc. This kills the 3 child processes of that supervisor one at a time and shows no result of one child being terminated.

- test_kill_one_process(process_name) - you can use this if you want to kill any of the 3 child processes

- show_children/0 - outputs the children names and pid.

When the application starts it starts a number of Supervisors. You can look at the supervision tree using a tool called “observer”. You can start observer from iex. Just type :observer.start. An app starts that has lots of tabs. Click on Applications and you can see the currently running process trees. See https://www.erlang.org/doc/apps/observer/observer_ug.html for more information.

:one_for_one

Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseOneForOne starts 3 child workers that use these names:

- :one_for_one_worker1

- :one_for_one_worker2

- :one_for_one_worker3

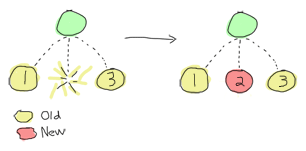

There’s a simple picture from the online book “Learn you some Erlang for great good!” that explains what we’ll see.

This shows that if there are 3 worker processes and #2 terminates then #1 and #3 are not impacted.

If test_kill_all/1 is called the output shows that only the process being killed terminates.

iex> SuperviseOneForOne.test_kill_all(:asc)

iex> SuperviseOneForOne.test_kill_all(:asc)

>>>>>>>> START one_for_one_worker1

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: one_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.214.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.213.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.212.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.212.0>

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: one_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.214.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.213.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.225.0>

<<<<< DONE one_for_one_worker1

>>>>>>>> START one_for_one_worker2

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: one_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.214.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.213.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.225.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.213.0>

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: one_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.214.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.226.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.225.0>

<<<<< DONE one_for_one_worker2

>>>>>>>> START one_for_one_worker3

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: one_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.214.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.226.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.225.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.214.0>

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: one_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.227.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.226.0>

Name: one_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.225.0>

<<<<< DONE one_for_one_worker3

:one_for_all

Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseOneForAll starts 3 child workers:

- :one_for_all_worker1

- :one_for_all_worker2

- :one_for_all_worker3

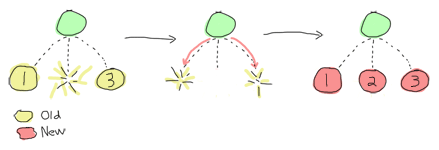

There’s a simple picture from “Learn you some Erlang for great good!” that explains what we’ll see.

So, in this case, if process #2 terminates then all the child processes are terminated with it. The Supervisor restarts all 3 processes in order: process #1, process #2, and then process #3.

If test_kill_all/1 is called the output shows that every child process terminates when any process terminates.

iex(1)> SuperviseOneForAll.test_kill_all(:asc)

>>>>>>>> START one_for_all_worker1

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: one_for_all_worker3, PID: #PID<0.233.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker2, PID: #PID<0.232.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker1, PID: #PID<0.231.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.231.0>

Terminating #PID<0.233.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_all_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.232.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_all_worker2"

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: one_for_all_worker3, PID: #PID<0.238.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker2, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker1, PID: #PID<0.236.0>

<<<<< DONE one_for_all_worker1

>>>>>>>> START one_for_all_worker2

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: one_for_all_worker3, PID: #PID<0.238.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker2, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker1, PID: #PID<0.236.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.237.0>

Terminating #PID<0.238.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_all_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.236.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_all_worker1"

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: one_for_all_worker3, PID: #PID<0.241.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker2, PID: #PID<0.240.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker1, PID: #PID<0.239.0>

<<<<< DONE one_for_all_worker2

>>>>>>>> START one_for_all_worker3

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: one_for_all_worker3, PID: #PID<0.241.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker2, PID: #PID<0.240.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker1, PID: #PID<0.239.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.241.0>

Terminating #PID<0.240.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_all_worker2"

Terminating #PID<0.239.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_all_worker1"

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: one_for_all_worker3, PID: #PID<0.244.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker2, PID: #PID<0.243.0>

Name: one_for_all_worker1, PID: #PID<0.242.0>

<<<<< DONE one_for_all_worker3

:rest_for_one

Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseRestForOne starts 3 child workers:

- :rest_for_one_worker1

- :rest_for_one_worker2

- :rest_for_one_worker3

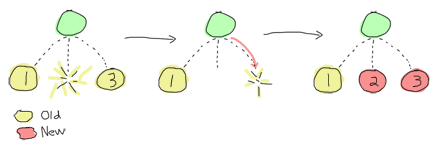

There’s a simple picture from “Learn you some Erlang for great good!” that explains what we’ll see.

There are 3 processes running under the supervisor. If process #2 terminates then process #3 is terminated since it started after process #2. Then process #2 is restarted followed by process #3.

If test_kill_all/1 is called the output shows different results depending on which child is terminated. If the first child, :rest_for_one_worker1 is terminated then the two other child processes terminate as well. This continues in a chain. If rest_for_one_worker2 is terminates it terminates rest_for_one_worker3 but :rest_for_one_worker1 is still running.

iex> SuperviseRestForOne.test_kill_all(:asc)

SuperviseRestForOne.test_kill_all(:asc)

>>>>>>>> START rest_for_one_worker1

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: rest_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.229.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.228.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.227.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.227.0>

Terminating #PID<0.229.0> with reason :shutdown and state "rest_for_one_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.228.0> with reason :shutdown and state "rest_for_one_worker2"

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: rest_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.239.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.238.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

<<<<< DONE rest_for_one_worker1

>>>>>>>> START rest_for_one_worker2

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: rest_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.239.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.238.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.238.0>

Terminating #PID<0.239.0> with reason :shutdown and state "rest_for_one_worker3"

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: rest_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.241.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.240.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

<<<<< DONE rest_for_one_worker2

>>>>>>>> START rest_for_one_worker3

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: rest_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.241.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.240.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.241.0>

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: rest_for_one_worker3, PID: #PID<0.242.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker2, PID: #PID<0.240.0>

Name: rest_for_one_worker1, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

<<<<< DONE rest_for_one_worker3

:rest_for_one but more interesting

The :rest_for_one section above showed how workers act if they are children of a Supervisor that uses :rest_for_one strategy. But you might think that it seemed a bit odd. Would you have a situation where you had 3 workers and the second depended on first and the third depended on second? Maybe.

A scenario you might see instead is that a Supervisor has 2 children. The first is a worker and the second is a Supervisor itself. That Supervisor, in turn, would start its own workers.

In the tree above Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels is a Supervisor with two children:

- :supervise_levels_worker1

- Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor

Since the rest for one strategy is used by Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels it means that all the child workers under the ChildSupervisor are dependent on :supervise_levels_worker1. If that process terminates the system would terminate the ChildSupervisor which would turn around and terminate all of its workers. Let’s test this manually this time.

iex> SuperviseLevels.children()

[

{Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor, #PID<0.221.0>,

:supervisor, [Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor]},

{:supervise_levels_worker1, #PID<0.220.0>, :worker,

[Supervise.Workers.SimpleWorker]}

]

iex(2)> SuperviseLevels.test_kill_one_process(:supervise_levels_worker1)

>>>>>>>> START supervise_levels_worker1

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor, PID: #PID<0.221.0>

Name: supervise_levels_worker1, PID: #PID<0.220.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.220.0>

Terminating #PID<0.224.0> with reason :shutdown and state "child_supervisor_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.223.0> with reason :shutdown and state "child_supervisor_worker2"

Terminating #PID<0.222.0> with reason :shutdown and state "child_supervisor_worker1"

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor, PID: #PID<0.229.0>

Name: supervise_levels_worker1, PID: #PID<0.228.0>

<<<<< DONE supervise_levels_worker1

This shows that if the child that was started first terminates then the second child and all of its workers are terminated. You can see that both pids are new by the end. Does the ChildSupervisor restart its workers in this case?

iex> ChildSupervisor.children()

[

{:child_supervisor_worker3, #PID<0.232.0>, :worker,

[Supervise.Workers.SimpleWorker]},

{:child_supervisor_worker2, #PID<0.231.0>, :worker,

[Supervise.Workers.SimpleWorker]},

{:child_supervisor_worker1, #PID<0.230.0>, :worker,

[Supervise.Workers.SimpleWorker]}

]

Yes, it did.

Don’t Kill a Supervisor

Can we kill the ChildSupervisor process. Yeah, of course. But its not a great test. Supervisors don’t have functionality beyond supervising. All of the interesting code lives down in OTP-land. In general, don’t worry about your Supervisor terminating inadvertently.

Other Supervisor Questions

Are restarts cumulative?

If a restart occurs for a process that is being supervised does that count as 1 just for itself or is it added to a total for all the processes being supervised? As it turns out, the max_restarts are cumulative. So if a Supervisor is supervising 4 children and has max_restarts set to 3 and all 4 children are killed then the Supervisor itself will restart.

iex> Supervise.MaxRestarts.SuperviseOneForOne.test_kill_all()

Before kill, Current Supervisor pid #PID<0.250.0>

Terminating #PID<0.263.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Terminating #PID<0.261.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Terminating #PID<0.262.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Elixir.Supervise.MaxRestarts.SuperviseOneForOne is starting

After kill, Current Supervisor pid #PID<0.264.0>

So because 4 processes restarted in less than 5 seconds the Supervisor was restarted.

Does Supervisor restarting processes because of one_for_all strategy count against max_restarts?

No. The Supervisor restarting processes because the strategy is set to :one_for_all doesn’t add up all the children that it restarts and use that to compare against :max_restarts. The restart count is the child process itself exiting. Not the Supervisor shutting it down because of this.

iex(1)> Supervise.MaxRestarts.SuperviseOneForAll.test_kill_one()

Before kill, Current Supervisor pid #PID<0.255.0>

Terminating #PID<0.265.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Terminating #PID<0.264.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Terminating #PID<0.263.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Terminating #PID<0.262.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Terminating #PID<0.261.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Terminating #PID<0.260.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Terminating #PID<0.259.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Terminating #PID<0.258.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

Terminating #PID<0.257.0> with reason :shutdown and state nil

After kill, Current Supervisor pid #PID<0.255.0>

Is it greater than max_restarts or equal to?

Greater than. Using the Supervise.MaxRestarts.SuperviseOneForOne which has 4 children we can kill three of its children and the supervisor is not restarted. This is because its max_restarts is set to 3. So 4 children have to be killed for the Supervisor itself to restart.

iex> Supervise.MaxRestarts.SuperviseOneForOne.test_kill_three()

Before kill, Current Supervisor pid #PID<0.239.0>

After kill, Current Supervisor pid #PID<0.239.0>

What About DynamicSupervisor?

A DynamicSupervisor is a separate variation of supervision in Elixir. With a Supervisor you ordinarily start with static children defined. With a DynamicSupervisor you start with no children and add (or remove) them over time. The only strategy available (at the moment) for DynamicSupervisor is :one_for_one.

You can add children to a Supervisor dynamically as well. So… hmmm… why would there be a DynamicSupervisor? One feature that’s in DynamicSupervisor is that you can specify the max children allowed. There are certain use cases where this is very useful.

In a DynamicSupervisor there is no ordering between children. In case of a shutdown the children are shutdown concurrently. This can also be quite useful for some use cases.

What Are Those Other Processes?

If you run the observer after starting up with iex -S mix then you see a tree (there may be more nodes on it but ignore that for now).

The SuperviseOneForAll, etc may look okay to you. But what’s Supervise.Supervisor? If you look in application.ex then you can see that’s how the rest of the tree is filled in.

defmodule Supervise.Application do

# See https://hexdocs.pm/elixir/Application.html

# for more information on OTP Applications

@moduledoc false

use Application

@impl true

def start(_type, _args) do

IO.puts("#{__MODULE__} is starting")

children = [

Supervise.Restart.StartupWait,

Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseOneForOne,

Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseRestForOne,

Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseOneForAll,

Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels,

Supervise.Types.SuperviseDynamically,

Supervise.RestartTypes.Permanent,

Supervise.RestartTypes.Temporary,

Supervise.RestartTypes.Transient,

Supervise.MaxRestarts.UsingOneForOne,

Supervise.MaxRestarts.UsingOneForAll,

# Supervise.Timeouts.LazySupervisor,

Supervise.Restart.WithWait

]

# See https://hexdocs.pm/elixir/Supervisor.html

# for other strategies and supported options

opts = [strategy: :one_for_one, name: Supervise.Supervisor]

Supervisor.start_link(children, opts)

end

end

You can see that Application is a Supervisor as well. It’s naming itself and setting a strategy of :one_for_one. You can read about Application in the Elixir documentation.

How is Application started? That’s done via the mix.exs file.

def application do

[

extra_applications: [:logger],

mod: {Supervise.Application, []}

]

end

The mod tells the “system” when you boot up run the start/2 function.

If you bring up observer you’ll see some root level processes that are not named and don’t correspond to modules in the test project. These processes are OTP level things. You can learn more if you are interested by reading through the code. It’s available at application_master.erl.

Building a Supervisor

When you write a Supervisor its got to have a few essential elements. The layout tends to be pretty standard. And it’s quite simple (ordinarily). Let’s start with a bare defmodule.

defmodule FirstSupervisor do

end

Use Supervisor

The first thing that you’ll do is include a use Supervisor line after the defmodule.

defmodule FirstSupervisor do

use Supervisor

end

The use is an Elixir Macro. It ends up calling the function using in the Supervisor module. This declares that this module implements the @behaviour Supervisor. It declares a childspec/1 function, builds a default childspec:

%{

id: __MODULE__,

start: {__MODULE__, :start_link, [init_arg]},

type: :supervisor

}

and uses the Supervisor.childspec/2 function to build the childspec for the Supervisor itself.

Create a start_link/1 function

There is a start_link/1 function that calls Supervisor.start_link/3. The first parameter is the module that implements the required Supervisor functionality. The second parameter is the init_arg. This is passed to the init/1 callback that the module must implement. The third parameter is a list that allows only one element to give the Supervisor a name. So, you might see something like: Supervisor.start_link(MODULE, :ok, [{:name, MODULE}]).

There’s also a start_link/2 where the list that contains the name isn’t passed in. If you use this you’ll have to identify the supervisor process by its pid.

defmodule FirstSupervisor do

use Supervisor

def start_link(_opts) do

Supervisor.start_link(__MODULE__, :ok, name: __MODULE__)

end

end

Create the init/1 callback function

The use Supervisor macro declared that the module implements the @behaviour Supervisor. The behaviour has one required callback - init/1.

The init callback must return {:ok, {:supervisor.sup_flags(), [:supervisor.child_spec()]}} or :ignore. What you’ll generally see in code is the last line in the init/1 callback is: Supervisor.init(children, opts). That function ensures that the correct data is returned.

The call to Supervisor.init/2 takes children and opts (a Keyword list). The children are a list of specs for the worker processes. The available options that can be passed in are:

-

:strategy-:one_for_one,:rest_for_one,:one_for_all(you can set this to simple_one_for_one but you’ll get a warning that the strategy is deprecated and you should be using DynamicSupervisor instead). If you don’t set a strategy then your app won’t start. -

:max_restarts- this is optional and defaults to 3. It’s the maximum number of restarts allowed for the children in a time frame. You can set it to 3 or higher. If you try to set it lower then the value is ignored. -

:max_seconds- this is optional and defaults to 5 (seconds). This is the time frame for the :max_restarts option. You can set this to any positive integer value. If you try zero or a negative value then your app won’t start.

Time Limits

- How long can start_link/3 run before there is a problem?

- How long can init/1 run before there is a problem?

There’s two modules in the project to help test this:

- Supervise.Timeouts.LazySupervisor - Supervisor started by Application

- Supervise.Timeouts.Lazy - Supervisor started by Supervise.Timeouts.LazySupervisor

By default the code is setup where LazySupervisor creates two Lazy processes - :lazy_start_link and :lazy_init. The :lazy_start_link waits 1 second before calling Supervisor.start_link/3. The :lazy_init waits 1 second after the init/1 function is called before proceeding with normal init functionality. When you start the app with iex -S mix you’ll see:

Elixir.Supervise.Timeouts.LazySupervisor is starting

Elixir.Supervise.Timeouts.Lazy.start_link/1 has name lazy_start_link

Elixir.Supervise.Timeouts.Lazy.start_link/1 will call Supervisor.start_link in 1000 ms

Elixir.Supervise.Timeouts.Lazy.init/1 will continue in 0 ms

Elixir.Supervise.Timeouts.Lazy.start_link/1 has name lazy_init

Elixir.Supervise.Timeouts.Lazy.start_link/1 will call Supervisor.start_link in 0 ms

Elixir.Supervise.Timeouts.Lazy.init/1 will continue in 1000 ms

So this works fine. But how far can this be pushed? Quite a bit, as it turns out. Exit the iex session and edit the lib/supervise/timeouts/lazy_supervisor.ex file and change the children in the init/1 function to:

children = [

lazy_spec(name: :lazy_start_link, start_link_delay: 1000),

lazy_spec(name: :lazy_init, init_delay: 60_000)

]

and you’ll find that works too. Likewise setting the :start_link_delay to 60_000 works. It’s odd but something to keep in mind.

Supervision when things go wrong

Too many restarts

A Supervisor defines the maximum number of restarts and the maximum time allowed for that number of restarts. It’s a rolling window. If the maximum time allowed is 5 seconds and a worker process terminates after 5 seconds and then doesn’t terminate again until 30 seconds later then the Supervisor has a count of 1 crash.

The ChildSupervisor has a function test_restarts(num_restarts). You pass in the integer value (at least 1). The function ensures that number of child processes restarts. The ChildSupervisor has max_restarts: 3, max_seconds: 1. So we expect that until we pass in a number > 3 the ChildSupervisor simply restarts the terminated worker.

iex(1)> ChildSupervisor.test_restarts(1)

:ok

iex(2)> ChildSupervisor.test_restarts(2)

:ok

iex(3)> ChildSupervisor.test_restarts(3)

:ok

iex(4)> ChildSupervisor.test_restarts(4)

Terminating #PID<0.259.0> with reason :shutdown and state "child_supervisor_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.257.0> with reason :shutdown and state "child_supervisor_worker2"

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor is starting

:ok

iex(5)> ChildSupervisor.show_children()

Name: child_supervisor_worker3, PID: #PID<0.264.0>

Name: child_supervisor_worker2, PID: #PID<0.263.0>

Name: child_supervisor_worker1, PID: #PID<0.262.0>

This shows that if the workers associated with the ChildSupervisor terminate frequently enough within a timeframe the ChildSupervisor itself shuts down. Since it has it’s own Supervisor - SuperviseLevels - it is restarted and then the workers are restarted as well.

Even though the ChildSupervisor has a strategy of :one_for_one if it shuts down because a child terminated and exceeded the thresholds then any other still running children of ChildSupervisor are shutdown. The ChildSupervisor then terminates and it’s restarted.

We can demonstrate too many but over a time period where the max_restarts is never exceeded for that period as well. We’ll terminate 3 children, sleep for 2 seconds, then terminate the 3 children again.

iex> ChildSupervisor.test_restarts(3); Process.sleep(2_000); ChildSupervisor.test_restarts(3)

:ok

The ChildSupervisor handled that fine. But if the sleep is shortened the ChildSupervisor is restarted.

iex> ChildSupervisor.test_restarts(3); Process.sleep(500); ChildSupervisor.test_restarts(3)

Terminating #PID<0.291.0> with reason :shutdown and state "child_supervisor_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.289.0> with reason :shutdown and state "child_supervisor_worker2"

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor is starting

But What if I did Kill a Supervisor?

Let’s first do this a smoother way. We can stop a Supervisor with Supervisor.stop/2.

iex> pid = Process.whereis(ChildSupervisor)

#PID<0.221.0>

iex> Supervisor.stop(pid, :normal)

Terminating #PID<0.224.0> with reason :shutdown and state "child_supervisor_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.223.0> with reason :shutdown and state "child_supervisor_worker2"

Terminating #PID<0.222.0> with reason :shutdown and state "child_supervisor_worker1"

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor is starting

:ok

You can see this acts just like the case of the worker restarts exceeding thresholds. In this case the ChildSupervisor stops all 3 workers and then stops. The Supervisor of the ChildSupervisor then restarts it.

Process.exit/2 is a good deal messier:

pid = Process.whereis(ChildSupervisor)

#PID<0.229.0>

iex(5)> Process.exit(pid, :kill)

Terminating #PID<0.233.0> with reason :killed and state "child_supervisor_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.231.0> with reason :killed and state "child_supervisor_worker2"

Terminating #PID<0.230.0> with reason :killed and state "child_supervisor_worker1"

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor is starting

true

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor is starting

iex(6)> Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor is starting

Terminating #PID<0.220.0> with reason :shutdown and state "supervise_levels_worker1"

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels is starting

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor is starting

Terminating #PID<0.242.0> with reason :shutdown and state "supervise_levels_worker1"

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels is starting

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor is starting

Terminating #PID<0.245.0> with reason :shutdown and state "supervise_levels_worker1"

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels is starting

Elixir.Supervise.Strategies.SuperviseLevels.ChildSupervisor is starting

Terminating #PID<0.248.0> with reason :shutdown and state "supervise_levels_worker1"

Terminating #PID<0.218.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_all_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.217.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_all_worker2"

Terminating #PID<0.216.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_all_worker1"

Terminating #PID<0.214.0> with reason :shutdown and state "rest_for_one_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.213.0> with reason :shutdown and state "rest_for_one_worker2"

Terminating #PID<0.212.0> with reason :shutdown and state "rest_for_one_worker1"

Terminating #PID<0.210.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_one_worker3"

Terminating #PID<0.209.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_one_worker2"

Terminating #PID<0.208.0> with reason :shutdown and state "one_for_one_worker1"

12:55:40.521 [notice] Application supervise exited: shutdown

And that’s a good reason to not kill a Supervisor process. The entire application was shutdown as the system thrashed a bit. You can see the ChildSupervisor is restarted multiple times. That causes SuperviseLevels to restart multiple times. SuperviseLevels lives under the Application. The bubbling up of these restarts lead to every process in the application being shut down.

Restart Values

One of the attributes in a child spec is a restart value. There are 3 types and the Supervisor handles them differently:

-

:permanent- this is the default and it’s what we’ve used to this point for all the workers created. It indicates the Supervisor should always restart this process. -

:temporary- the child process is never restarted, regardless of the supervision strategy: any termination (even abnormal) is considered successful. -

:transient- the child process is restarted only if it terminates abnormally, i.e., with an exit reason other than :normal, :shutdown, or {:shutdown, term}.

Testing

:permanent

The tests described above all used permanent so there’s no need to run special tests for this restart value.

:temporary

Running the test_kill_all/1 function for Temporary gives us these results:

iex> Temporary.test_kill_all

>>>>>>>> START restart_temporary_worker1

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: restart_temporary_worker3, PID: #PID<0.233.0>

Name: restart_temporary_worker2, PID: #PID<0.232.0>

Name: restart_temporary_worker1, PID: #PID<0.231.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.231.0>

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: restart_temporary_worker3, PID: #PID<0.233.0>

Name: restart_temporary_worker2, PID: #PID<0.232.0>

<<<<< DONE restart_temporary_worker1

>>>>>>>> START restart_temporary_worker2

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: restart_temporary_worker3, PID: #PID<0.233.0>

Name: restart_temporary_worker2, PID: #PID<0.232.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.232.0>

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: restart_temporary_worker3, PID: #PID<0.233.0>

<<<<< DONE restart_temporary_worker2

>>>>>>>> START restart_temporary_worker3

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: restart_temporary_worker3, PID: #PID<0.233.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.233.0>

------ Show children after stop ------

<<<<< DONE restart_temporary_worker3

You can see the Temporary Supervisor loses all of its children as the test loops killing each in turn. They do not restart. Does this kill the Supervisor?

iex> Process.whereis(Temporary)

#PID<0.230.0>

iex> Supervisor.count_children(Temporary)

%{active: 0, specs: 0, supervisors: 0, workers: 0}

Nope its running. But it has no children now. We can re-add a worker to it if we wish.

iex> Supervisor.start_child(Temporary, SimpleWorker.build_spec(:restart_temporary_worker1, :temporary))

{:ok, #PID<0.257.0>}

iex> Supervisor.count_children(Supervise.RestartTypes.Temporary)

%{active: 1, specs: 1, supervisors: 0, workers: 1}

:transient

The Transient Supervisor is going to behave like the Permanent Supervisor in the first test. This is because we are terminating the workers abnormally. Since that is the case the Permanent Supervisor restarts the worker.

Transient.test_kill_all()

>>>>>>>> START restart_transient_worker1

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: restart_transient_worker3, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker2, PID: #PID<0.236.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker1, PID: #PID<0.235.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.235.0>

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: restart_transient_worker3, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker2, PID: #PID<0.236.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker1, PID: #PID<0.240.0>

<<<<< DONE restart_transient_worker1

>>>>>>>> START restart_transient_worker2

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: restart_transient_worker3, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker2, PID: #PID<0.236.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker1, PID: #PID<0.240.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.236.0>

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: restart_transient_worker3, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker2, PID: #PID<0.241.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker1, PID: #PID<0.240.0>

<<<<< DONE restart_transient_worker2

>>>>>>>> START restart_transient_worker3

------ Show children before stop ------

Name: restart_transient_worker3, PID: #PID<0.237.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker2, PID: #PID<0.241.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker1, PID: #PID<0.240.0>

------ Stopping one child ------

Killing the process #PID<0.237.0>

------ Show children after stop ------

Name: restart_transient_worker3, PID: #PID<0.242.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker2, PID: #PID<0.241.0>

Name: restart_transient_worker1, PID: #PID<0.240.0>

<<<<< DONE restart_transient_worker3

And the Transient Supervisor remains up and running - with 3 children.

iex> Process.whereis(Transient)

#PID<0.234.0>

iex> Supervisor.count_children(Transient)

%{active: 3, specs: 3, supervisors: 0, workers: 3}

Real Problems

Why Can’t I Configure a Delay When Worker is Restarted?

This has come up many times. The problem that people run into is that a worker terminates because of a network connection problem. The developer knows this happens occasionally. They know that if they can just wait a few seconds before a restart then the connection is probably okay. However, there’s no options available that lets the developer configure a Supervisor to add in a restart delay. And if the worker is restarted really quickly then its easy for it to exceed the :max_retries allowed by its Supervisor. Thus crashing the Supervisor and possibly taking the entire application down.

There are a couple of approaches to resolving this issue. One approach to create a Delay module.

The basic idea is that in the start_link for the process we want to delay we call into the Delay module. It contains state that can identify whether this is the first time starting this process or a restart. If its a restart then it will delay the process startup.

Note: The brod Erlang Kafka library includes its own Supervisor implementation. This has some of the delay restart functionality used with :erlang.send_after.

The sample project has a demonstration of this in Supervise.Restart.StartupWait. A new GenServer module - Supervise.Workers.WaitWorker - calls the register/1 function in StartupWait in its start_link/1 function. This will ensure that a delay occurs before the WaitWorker process can be created.

References

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: